For whom is the funhouse fun? Perhaps for lovers. For Ambrose it is a place of fear and confusion. He has come to the seashore with his family for the holiday, the occasion of their visit is Independence Day, the most important secular holiday of the United States of America. A single straight underline is the manuscript mark for italic type, which in turn is the printed equivalent to oral emphasis of words and phrases as well as the customary type for titles of complete works, not to mention. Italics are also employed, in fiction stories especially, for “outside,” intrusive, or artificial voices, such as radio announcements, the texts of telegrams and newspaper articles, et cetera. They should be used sparingly. If passages originally in roman type are italicized by someone repeating them, it’s customary to acknowledge the fact. Italics mine.

Ambrose was “at that awkward age.” His voice came out high-pitched as a child’s if he let himself get carried away; to be on the safe side, therefore, he moved and spoke with deliberate calm and adult gravity. Talking soberly of unimportant or irrelevant matters and listening consciously to the sound of your own voice are useful habits for maintaining control in this difficult interval. En route to Ocean City he sat in the back seat of the family car with his brother Peter, age fifteen, and Magda G —‘ age fourteen, a pretty girl and exquisite young lady, who lived not far from them on B — Street in the town of D —, Maryland. Initials, blanks, or both were often substituted for proper names in nineteenth-century fiction to enhance the illusion of reality. It is as if the author felt it necessary to delete the names for reasons of tact or legal liability. Interestingly, as with other aspects of realism, it is an illusion that is being enhanced, by purely artificial means. Is it likely, does it violate the principle of verisimilitude, that a thirteen-year-old boy could make such a sophisticated observation? A girl of fourteen is the psychological coeval of a boy of fifteen or sixteen; a thirteen-year-old boy, therefore, even one precocious in some other respects, might be three years her emotional junior.

Thrice a year — on Memorial, Independence, and Labor Days — the family visits Ocean City for the afternoon and evening. When Ambrose and Peter’s father was their age, the excursion was made by train, as mentioned in the novel The 42nd Parallel by John Dos Passos. Many families from the same neighborhood used to travel together, with dependent relatives and often with Negro servants; schoolfuls of children swarmed through the railway cars; everyone shared everyone else’s Maryland fried chicken, Virginia ham, deviled eggs, potato salad, beaten biscuits, iced tea. Nowadays (that is, in 19– , the year of our story) the journey is made by automobile — more comfortably and quickly though without the extra fun though without the camaraderie of a general excursion. It’s all part of the deterioration of American life, their father declares; Uncle Karl supposes that when the boys take their families to Ocean City for the holidays they’ll fly in Autogiros. Their mother, sitting in the middle of the front seat like Magda in the second, only with her arms on the seat-back behind the men’s shoulders, wouldn’t want the good old days back again, the steaming trains and stuffy long dresses; on the other hand she can do without Autogiros, too, if she has to become a grandmother to fly in them.

Description of physical appearance and mannerisms is one of several standard methods of characterization used by writers of fiction. It is also important to “keep the senses operating”; when a detail from one of the five senses, say visual, is “crossed” with a detail from another, say auditory, the reader’s imagination is oriented to the scene, perhaps unconsciously. This procedure may he compared to the way surveyors and navigators determine their positions by two or more compass bearings, a process known as triangulation. The brown hair on Ambrose’s mother’s forearms gleamed in the sun like. Though right-handed, she took her left arm from the seat back to press the dashboard cigar lighter for Uncle Karl. When the glass bead in its handle glowed red, the lighter was ready for use. The smell of Uncle Karl’s cigar smoke reminded one of. The fragrance of the ocean came strong to the picnic ground where they always stopped for lunch, two miles inland from Ocean City Having to pause for a full hour almost within sound of the breakers was difficult for Peter and Ambrose when they were younger; even at their present age it was not easy to keep their anticipation, stimulated by the briny spume, from turning into short temper. The Irish author James Joyce, in his unusual novel entitled Ulysses, now available in this country uses the adjectives snot-green and scrotum-tightening to describe the sea. Visual, auditory tactile, olfactory, gustatory Peter and Ambrose’s father, while steering their black 1936 LaSalle sedan with one hand, could with the other remove the first cigarette from a white pack of Lucky Strikes and, more remarkably, light it with a match forefingered from its book and thumbed against the flint paper without being detached. The matchbook cover merely advertised U.S. War Bonds and Stamps. A fine metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech, in addition to its obvious “first-order” relevance to the thing it describes, will be seen upon reflection to have a second order of significance: it may be drawn from the milieu of the action, for example, or be particularly appropriate to the sensibility of the narrator, even hinting to the reader things of which the narrator is unaware; or it may cast further and subtler lights upon the things it describes, sometimes ironically qualifying the more evident sense of the comparison.

To say that Ambrose’s and Peter’s mother was pretty is to accomplish nothing; the reader may acknowledge the proposition, but his imagination is not engaged. Besides, Magda was also pretty, yet in an altogether different way. Although she lived on B — Street she had very good manners and did better than average in school. Her figure was very well developed for her age. Her right hand lay casually on the plush upholstery of the seat, very near Ambrose’s left leg, on which his own hand rested. The space between their legs, between her right and his left leg, was out of the line of sight of anyone sitting on the other side of Magda, as well as anyone glancing into the rear-view mirror. Uncle Karl’s face resembled Peter’s — rather, vice versa. Both had dark hair and eyes, short husky statures, deep voices. Magda’s left hand was probably in a similar position on her left side. The boys’ father is difficult to describe; no particular feature of his appearance or manner stood out. He wore glasses and was principal of a T County grade school. Uncle Karl was a masonry contractor.

Although Peter must have known as well as Ambrose that the latter, because of his position in the car, would be first to see the electrical towers of the power plant at V —, the halfway point of their trip, he leaned forward and slightly toward the center of the car and pretended to be looking for them through the flat pinewoods and tuckahoe creeks along the highway. For as long as the boys could remember, “Looking for the Towers” had been a feature of the first half of their excursions to Ocean City, “looking for the standpipe” of the second. Though the game was childish, their mother preserved the tradition of rewarding the first to see the Towers with a candy-bar or piece of fruit. She insisted now that Magda play the game; the prize, she said, was “something hard to get nowadays.” Ambrose decided not to join in; he sat far back in his seat. Magda, like Peter, leaned forward. Two sets of straps were discernible through the shoulders of her sun dress; the inside right one, a brassiere-strap, was fastened or shortened with a small safety pin. The right armpit of her dress, presumably the left as well, was damp with perspiration. The simple strategy for being first to espy the Towers, which Ambrose had understood by the age of four, was to sit on the right-hand side of the car. Whoever sat there, however, had also to put up with the worst of the sun, and so Ambrose, without mentioning the matter, chose sometimes the one and sometimes the other. Not impossibly Peter had never caught on to the trick, or thought that his brother hadn’t simply because Ambrose on occasion preferred shade to a Baby Ruth or tangerine.

The shade-sun situation didn’t apply to the front seat, owing to the windshield; if anything the driver got more sun, since the person on the passenger side not only was shadowed below by the door and dashboard but might swing down his sun visor all the way too.

“Is that them?” Magda asked. Ambrose’s mother teased the boys for letting Magda win, insinuating that “somebody [had] a girlfriend.” Peter and Ambrose’s father reached a long thin arm across their mother to butt his cigarette in the dashboard ashtray, under the lighter. The prize this time for seeing the Towers first was a banana. Their mother bestowed it after chiding their father for wasting a half-smoked cigarette when everything was so scarce. Magda, to take the prize, moved her hand from so near Ambrose’s that he could have touched it as though accidentally. She offered to share the prize, things like that were so hard to find; but everyone insisted it was hers alone. Ambrose’s mother sang an iambic trimeter couplet from a popular song, femininely rhymed:

“What’s good is in the Army;

What’s left will never harm me.

Uncle Karl tapped his cigar ash out the ventilator window; some particles were sucked by the slipstream back into the car through the rear window on the passenger side. Magda demonstrated her ability to hold a banana in one hand and peel it with her teeth. She still sat forward; Ambrose pushed his glasses back onto the bridge of his nose with his left hand, which he then negligently let fall to the seat cushion immediately behind her. He even permitted the single hair, gold, on the second joint of his thumb to brush the fabric of her skirt. Should she have sat back at that instant, his hand would have been caught under her.

Plush upholstery prickles uncomfortably through gabardine slacks in the July sun. The function of the beginning of a story is to introduce the principal characters, establish their initial relationships, set the scene for the main action, expose the background of the situation if necessary. plant motifs and foreshadowings where appropriate, and initiate the first complication or whatever of the “rising action.” Actually, if one imagines a story called “The Funhouse,” or “Lost in the Funhouse,” the details of the drive to Ocean City don’t seem especially relevant. The beginning should recount the events between Ambrose’s first sight of the funhouse early in the afternoon and his entering it with Magda and Peter in the evening. The middle would narrate all relevant events from the time he goes in to the time he loses his way; middles have the double and contradictory function of delaying the climax while at the same time preparing the reader for it and fetching him to it. Then the ending would tell what Ambrose does while he’s lost, how he finally finds his way out, and what everybody makes of the experience. So far there’s been no real dialogue, very little sensory detail, and nothing in the way of a theme. And a long time has gone by already without anything happening; it makes a person wonder. We haven’t even reached Ocean City yet: we will never get out of the funhouse.

The more closely an author identifies with the narrator, literally or metaphorically, the less advisable it is, as a rule, to use the first-person narrative viewpoint. Once three years previously the young people aforementioned played Niggers and Masters in the backyard; when it was Ambrose’s turn to be Master and theirs to be Niggers Peter had to go serve his evening papers; Ambrose was afraid to punish Magda alone, but she led him to the whitewashed Torture Chamber between the woodshed and the privy in the Slaves Quarters; there she knelt sweating among bamboo rakes and dusty Mason jars, pleadingly embraced his knees, and while bees droned in the lattice as if on an ordinary summer afternoon, purchased clemency at a surprising price set by herself. Doubtless she remembered nothing of this event; Ambrose on the other hand seemed unable to forget the least detail of his life. He even recalled how, standing beside himself with awed impersonality in the reeky heat, he’d stared the while at an empty cigar box in which Uncle Karl kept stone-cutting chisels: beneath the words El Producto, a laureled, loose-toga’d lady regarded the sea from a marble bench; beside her, forgotten. or not yet turned to, was a five-stringed lyre. Her chin reposed on the back of her right hand; her left depended negligently from the bench-arm. The lower half of scene and lady was peeled away; the words EXAMINED BY — were inked there into the wood. Nowadays cigar boxes are made of pasteboard. Ambrose wondered what Magda would have done, Ambrose wondered what Magda would do when she sat back on his hand as he resolved she should. Be angry Make a teasing joke of it. Give no sign at all. For a long time she leaned forward, playing cow-poker with Peter against Uncle Karl and Mother and watching for the first sign of Ocean City. At nearly the same instant, picnic ground and Ocean City standpipe hove into view; an Amoco filling station on their side of the road cost Mother and Uncle Karl fifty cows and the game; Magda bounced back, clapping her right hand on Mother’s right arm; Ambrose moved clear “in the nick of time.~~

At this rate our hero, at this rate our protagonist will remain in the funhouse forever. Narrative ordinarily consists of alternating dramatization and summarization. One symptom of nervous tension, paradoxically, is repeated and violent yawning; neither Peter nor Magda nor Uncle Karl nor Mother reacted in this manner. Although they were no longer small children, Peter and Ambrose were each given a dollar to spend on boardwalk amusements in addition to what money of their own they’d brought along. Magda too, though she protested she had ample spending money. The boys’ mother made a little scene out of distributing the bills; she pretended that her sons and Magda were small children and cautioned them not to spend the sum too quickly or in one place. Magda promised with a merry laugh and, having both hands free, took the bill with her left. Peter laughed also and pledged in a falsetto to be a good boy. His imitation of a child was not clever. The boys’ father was tall and thin, balding, fair-complexioned. Assertions of that sort are not effective; the reader may acknowledge the proposition, but. We should be much farther along than we are; something has gone wrong; not much of the preliminary rambling seems relevant. Yet everyone begins in the same place; how is it that most go along without difficulty but a few lose their way?

“Stay out from under the boardwalk,” Uncle Karl growled from the side of his mouth. The boys’ mother pushed his shoulder in mock annoyance. They were all standing before Fat May the Laughing Lady who advertised the funhouse. Larger than life, Fat May mechanically shook, rocked on her heels, slapped her thighs while recorded laughter — uproarious, female — came amplified from a hidden loudspeaker. It chuckled, wheezed, wept; tried in vain to catch its breath; tittered, groaned, exploded raucous and anew. You couldn’t hear it without laughing yourself, no matter how you felt. Father came back from talking to a Coast-Guardsman on duty and reported that the surf was spoiled with crude oil from tankers recently torpedoed offshore. Lumps of it, difficult to remove, made tarry tidelines on the beach and stuck on swimmers. Many bathed in the surf nevertheless and came out speckled; others paid to use a municipal pool and only sunbathed on the beach. We would do the latter. We would do the latter. We would do the latter.

Under the boardwalk, matchbook covers, grainy other things. What is the story’s theme? Ambrose is ill. He perspires in the dark passages, candied apples-on-a-stick, delicious-looking, disappointing to eat. Funhouses need men’s and ladies’ rooms at intervals. Others perhaps have also vomited in corners and corridors; may even have had bowel movements liable to be stepped in in the dark. The word fuck suggests suction and/or and/or flatulence. Mother and Father; grandmothers and grandfathers on both sides; great-grandmothers and great-grandfathers on four sides, et cetera. Count a generation as thirty years: in approximately the year when Lord Baltimore was granted charter to the province of Maryland by Charles I, five hundred twelve women — English, Welsh, Bavarian, Swiss — of every class and character, received into themselves the penises the intromittent organs of five hundred twelve men, ditto, in every circumstance and posture, to conceive the five hundred twelve ancestors and the two hundred fifty-six ancestors of the et cetera et cetera et cetera et cetera et cetera et cetera et cetera et cetera of the author, of the narrator, of this story, Lost in the Funhouse. In alleyways, ditches, canopy beds, pinewoods, bridal suites, ship’s cabins, coach-and-fours, coaches.and four sultry toolsheds; on the cold sand under boardwalks, littered with El Producto cigar butts, treasured with Lucky Strike cigarette stubs, Coca-Cola caps, gritty turds, cardboard lollipop sticks, matchbook covers warning that A Slip of the Lip Can Sink a Ship. The shluppish whisper, continuous as seawash round the globe, tidelike falls and rises with the circuit of dawn and dusk.

Magda’s teeth. She was left-handed. Perspiration. They’ve gone all the way, through, Magda and Peter, they’ve been waiting for hours with Mother and Uncle Karl while Father searches for his lost son; they draw french-fried potatoes from a paper cup and shake their heads. They’ve named the children they’ll one day have and bring to Ocean City on holidays. Can spermatozoa properly be thought of as male animalcules when there are no female spermatozoa? They grope through hot, dark windings, past Love’s Tunnel’s fearsome obstacles. Some perhaps lose their way.

Peter suggested then and there that they do the funhouse; he had been through it before, so had Magda, Ambrose hadn’t and suggested, his voice cracking on account of Fat May’s laughter, that they swim first. All were chuckling, couldn’t help it; Ambrose’s father, Ambrose’s and Peter’s father came up grinning like a lunatic with two boxes of syrup-coated popcorn, one for Mother, one for Magda; the men were to help themselves. Ambrose walked on Magda’s right; being by nature left-handed, she carried the box in her left hand. Up front the situation was reversed.

“What are you limping for?” Magda inquired of Ambrose. He supposed in a husky tone that his foot had gone to sleep in the car. Her teeth flashed. “Pins and needles?” It was the honeysuckle on the lattice of the former privy that drew the bees. Imagine being stung there. How long is this going to take?

The adults decided to forgo the pool; but Uncle Karl insisted they change into swimsuits and do the beach. “He wants to watch the pretty girls,” Peter teased, and ducked behind Magda from Uncle Karl’s pretended wrath. “You’ve got all the pretty girls you need right here,” Magda declared, and Mother said: “Now that’s the gospel truth.” Magda scolded Peter, who reached over her shoulder to sneak some popcorn. “Your brother and father aren’t getting any” Uncle Karl wondered if they were going to have fireworks that night, what with the shortages. It wasn’t the shortages, Mr. M — replied; Ocean City had fireworks from pre-war. But it was too risky on account of the enemy submarines, some people thought.

“Don’t seem like Fourth of July without fireworks,” said Uncle Karl. The inverted tag in dialogue writing is still considered permissible with proper names or epithets, but sounds old-fashioned with personal pronouns. “We’ll have ‘em again soon enough,” predicted the boys’ father. Their mother declared she could do without fireworks: they reminded her too much of the real thing. Their father said all the more reason to shoot off a few now and again. Uncle Karl asked rhetorically who needed reminding, just look at people’s hair and skin.

“The oil, yes,” said Mrs. M

Ambrose had a pain in his stomach and so didn’t swim but enjoyed watching the others. He and his father burned red easily Magda’s figure was exceedingly well developed for her age. The too declined to swim, and got mad, and became angry when Peter attempted to drag her into the pool. She always swam, he insisted; what did she mean not swim? Why did a person come to Ocean City?

“Maybe I want to lay here with Ambrose,” Magda teased.

Nobody likes a pedant.

“Aha,” said Mother. Peter grabbed Magda by one ankle and ordered Ambrose to grab the other. She squealed and rolled over on the beach blanket. Ambrose pretended to help hold her back. Her tan was darker than even Mother’s and Peter’s. “Help out, Uncle Karl!” Peter cried. Uncle Karl went to seize the other ankle. Inside the top of her swimsuit, however, you could see the line where the sunburn ended and, when she hunched her shoulders and squealed again, one nipple’s auburn edge. Mother made them behave themselves. “You should certainly know,” she said to Uncle Karl. Archly “That when a lady says she doesn’t feel like swimming, a gentleman doesn’t ask questions.” Uncle Karl said excuse him; Mother winked at Magda; Ambrose blushed; stupid Peter kept saying “Phooey on feel like!” and tugging at Magda’s ankle; then even he got the point, and cannonballed with a holler into the pool.

“I swear,” Magda said, in mock in feigned exasperation.

The diving would make a suitable literary symbol. To go off the high board you had to wait in a line along the poolside and up the ladder. Fellows tickled girls and goosed one another and shouted to the ones at the top to hurry up, or razzed them for bellyfloppers. Once on the springboard some took a great while posing or clowning or deciding on a dive or getting up their nerve; others ran right off. Especially among the younger fellows the idea was to strike the funniest pose or do the craziest stunt as you fell, a thing that got harder to do as you kept on and kept on. But whether you hollered Geronimo! or Sieg heil!, held your nose or “rode a bicycle,” pretended to be shot or did a perfect jackknife or changed your mind halfway down and ended up with nothing, it was over in two seconds, after all that wait. Spring, pose, splash. Spring, neat-o, splash, Spring, aw fooey, splash.

The grown-ups had gone on; Ambrose wanted to converse with Magda; she was remarkably well developed for her age; it was said that that came from rubbing with a turkish towel, and there were other theories. Ambrose could think of nothing to say except how good a diver Peter was, who was showing off for her benefit. You could pretty well tell by looking at their bathing suits and arm muscles how far along the different fellows were. Ambrose was glad he hadn’t gone in swimming, the cold water shrank you up so. Magda pretended to be uninterested in the diving; she probably weighed as much as he did. If you knew your way around in the funhouse like your own bedroom, you could wait until a girl came along and then slip away without ever getting caught, even if her boyfriend ~ right with her. She’d think he did it! It would be better to be the boyfriend, and act outraged, and tear the funhouse apart.

Not act; be.

“He’s a master diver,” Ambrose said. In feigned admiration. “You really have to slave away at it to get that good.” What would it matter anyhow if he asked her right out whether she remembered, even teased her with it as Peter would have?

There’s no point in going farther; this isn’t getting anybody anywhere; they haven’t even come to the funhouse yet. Ambrose is off the track, in some new or old part of the place that’s not supposed to be used; he strayed into it by some one-in-a-million chance, like the time the roller-coaster car left the tracks in the nineteen-teens against all the laws of physics and sailed over the boardwalk in the dark. And they can’t locate him because they don’t know where to look. Even the designer and operator have forgotten this other part, that winds around on itself like a whelk shell. That winds around the right part like the snakes on Mercury’s caduceus. Some people, perhaps, don’t “hit their stride” until their twenties, when the growing-up business is over and women appreciate other things besides wisecracks and teasing and strutting. Peter didn’t have one-tenth the imagination he had, not one-tenth. Peter did this naming-their-children thing as a joke, making up names like Aloysius and Murgatroyd, but Ambrose knew exactly how it would feel to be married and have children of your own, and be a loving husband and father, and go comfortably to work in the mornings and to bed with your wife at night, and wake up with her there. With a breeze coming through the sash and birds and mockingbirds singing in the Chinese-cigar trees. His eyes watered, there aren’t enough ways to say that. He would be quite famous in his line of work. Whether Magda was his wife or not, one evening when he was wise-lined and gray at the temples he’d smile gravely, at a fashionable dinner party and remind her of his youthful passion. The time they went with his family to Ocean City; the erotic fantasies he used to have about her. How long ago it seemed, and childish! Yet tender, too, n’est-ce pas? Would she have imagined that the world-famous whatever remembered how many strings were on the lyre on the bench beside the girl on the label of the cigar box he’d stared at in the tool shed at age ten while, she, age eleven. Even then he had felt wise beyond his years; he’d stroked her hair and said in his deepest voice and correctest English, as to a dear child: “I shall never forget this moment.”

But though he had breathed heavily, groaned as if ecstatic, what he’d really felt throughout was an odd detachment, as though someone else were Master. Strive as he might to be transported, he heard his mind take notes upon the scene: This is what they call passion. I am experiencing it. Many of the digger machines were out of order in the penny arcades and could not be repaired or replaced for the duration. Moreover the prizes, made now in USA, were less interesting than formerly, pasteboard items for the most part, and some of the machines wouldn’t work on white pennies. The gypsy fortuneteller machine might have provided a foreshadowing of the climax of this story if Ambrose had operated it. It was even dilapidateder than most: the silver coating was worn off the brown metal handles, the glass windows around the dummy were cracked and taped, her kerchiefs and silks long faded. If a man lived by himself, he could take a department-store mannequin with flexible joints and modify her in certain ways. However: by the time he was that old he’d have a real woman. There was a machine that stamped your name around a white-metal coin with a star in the middle: A . His son would be the second, and when the lad reached thirteen or so he would put a strong arm around his shoulder and tell him calmly: “It is perfectly normal. We have all been through it. It will not last forever.” Nobody knew how to be what they were right. He’d smoke a pipe, teach his son how to fish and softcrab, assure him he needn’t worry about himself. Magda would certainly give, Magda would certainly yield a great deal of milk, although guilty of occasional solecisms. It don’t taste so bad. Suppose the lights came on now!

The day wore on. You think you’re yourself, but there are other persons in you. Ambrose gets hard when Ambrose doesn’t want to, and obversely. Ambrose watches them disagree; Ambrose watches him watch. In the fun-house mirror room you can’t see yourself go on forever, because no matter how you stand, your head gets in the way. Even if you had a glass periscope, the image of your eye would cover up the thing you really wanted to see. The police will come; there’ll be a story in the papers. That must be where it happened. Unless he can find a surprise exit, an unofficial backdoor or escape hatch opening on an alley, say, and then stroll up to the family in front of the funhouse and ask where everybody’s been; he’s been out of the place for ages. That’s just where it happened, in that last lighted room: Peter and Magda found the right exit; he found one that you weren’t supposed to find and strayed off into the works somewhere. In a perfect funhouse you’d be able to go only one way, like the divers off the high board; getting lost would be impossible; the doors and halls would work like minnow traps on the valves in veins.

On account of German U-boats, Ocean City was “browned out”: streetlights were shaded on the seaward side; shop-windows and boardwalk amusement places were kept dim, not to silhouette tankers and Liberty ships for torpedoing. In a short story about Ocean City, Maryland, during World War II, the author could make use of the image of sailors on leave in the penny arcades and shooting galleries, sighting through the crosshairs of toy machine guns at swastika’d subs, while out in the black Atlantic a U-boat skipper squints through his periscope at real ships outlined by the glow of penny arcades. After dinner the family strolled back to the amusement end of the boardwalk. The boys’ father had burnt red as always and was masked with Noxzema, a minstrel in reverse. The grownups stood at the end of the boardwalk where the Hurricane of ‘33 had cut an inlet from the ocean to Assawoman Bay.

“Pronounced with a long o,” Uncle Karl reminded Magda with a wink. His shirt sleeves were rolled up; Mother punched his brown biceps with the arrowed heart on it and said his mind was naughty. Fat May’s laugh came suddenly from the funhouse, as if she’d just got the joke; the family laughed too at the coincidence. Ambrose went under the boardwalk to search for out-of-town matchbook covers with the aid of his pocket flashlight; he looked out from the edge of the North American continent and wondered how far their laughter carried over the water. Spies in rubber rafts; survivors in lifeboats. If the joke had been beyond his understanding, he could have said:

“The laughter was over his head.” And let the reader see the serious wordplay on second reading.

He turned the flashlight on and then off at once even before the woman whooped. He sprang away, heart athud, dropping the light. What had the man grunted? Perspiration drenched and chilled him by the time he scrambled up to the family. “See anything?” his father asked. His voice wouldn’t come; he shrugged and violently brushed sand from his pants legs.

“Let’s ride the old flying horses!” Magda cried. I’ll never be an author. It’s been forever already, everybody’s gone home, Ocean City’s deserted, the ghost-crabs are tickling across the beach and down the littered cold streets. And the empty halls of clapboard hotels and abandoned funhouses. A tidal wave; an enemy air raid; a monster-crab swelling like an island from the sea. The inhabitants fled in terror. Magda clung to his trouser leg; he alone knew the maze’s secret. “He gave his life that we might live,” said Uncle Karl with a scowl of pain, as he. The fellow’s hands had been tattooed; the woman’s legs, the woman’s fat white legs had. An astonishing coincidence. He yearned to tell Peter. He wanted to throw up for excitement. They hadn’t even chased him. He wished he were dead.

One possible ending would be to have Ambrose come across another lost person in the dark. They’d match their wits together against the funhouse, struggle like Ulysses past obstacle after obstacle, help and encourage each other. Or a girl. By the time they found the exit they’d be closest friends, sweethearts if it were a girl; they’d know each other’s inmost souls, be bound together by the cement of shared adventure; then they’d emerge into the light and it would turn out that his friend was a Negro. A blind girl. President Roosevelt’s son. Ambrose’s former archenemy

Shortly after the mirror room he’d groped along a musty corridor, his heart already misgiving him at the absence of phosphorescent arrows and other signs. He’d found a crack of light — not a door, it turned out, but a seam between the ply board wall panels — and squinting up to it, espied a small old man, in appearance not unlike the photographs at home of Ambrose’s late grandfather, nodding upon a stool beneath a bare, speckled bulb. A crude panel of toggle- and knife-switches hung beside the open fuse box near his head; elsewhere in the little room were wooden levers and ropes belayed to boat cleats. At the time, Ambrose wasn’t lost enough to rap or call; later he couldn’t find that crack. Now it seemed to him that he’d possibly dozed off for a few minutes somewhere along the way; certainly he was exhausted from the afternoon’s sunshine and the evening’s problems; he couldn’t be sure he hadn’t dreamed part or all of the sight. Had an old black wall fan droned like bees and shimmied two flypaper streamers? Had the funhouse operator —gentle, somewhat sad and tired-appearing, in expression not unlike the photographs at home of Ambrose’s late Uncle Konrad — murmured in his sleep? Is there really such a person as Ambrose, or is he a figment of the author’s imagination? Was it Assawoman Bay or Sinepuxent? Are there other errors of fact in this fiction? Was there another sound besides the little slap slap of thigh on ham, like water sucking at the chine-boards of a skiff?

When you’re lost, the smartest thing to do is stay put till you’re found hollering if necessary But to holler guarantees humiliation as well as rescue; keeping silent permits some saving of face — you can act surprised at the fuss when your rescuers find you and swear you weren’t lost, if they do. What’s more you might find your own way yet, however belatedly.

“Don’t tell me your foot’s still asleep!” Magda exclaimed as the three young people walked from the inlet to the area set aside for ferris wheels, carrousels, and other carnival rides, they having decided in favor of the vast and ancient merry-go-round instead of the funhouse. What a sentence, everything was wrong from the outset. People don’t know what to make of him, he doesn’t know what to make of himself, he’s only thirteen, athletically and socially inept, not astonishingly bright, but there are antennae; he has.., some sort of receivers in his head; things speak to him, he understands more than he should, the world winks at him through its objects, grabs grinning at his coat. Everybody else is in on some secret he doesn’t know; they’ve forgotten to tell him. Through simple procrastination his mother put off his baptism until this year. Everyone else had it done as a baby; he’d assumed the same of himself, as had his mother, so she claimed, until it was time for him to join Grace Methodist-Protestant and the oversight came out. He was mortified, but pitched sleepless through his private catechizing, intimidated by the ancient mysteries, a thirteen year old would never say that, resolved to experience conversion like St. Augustine. When the water touched his brow and Adam’s sin left him, he contrived by a strain like defecation to bring tears into his eyes — but felt nothing. There was some simple, radical difference about him; he hoped it was genius, feared it was madness, devoted himself to amiability and inconspicuousness. Alone on the seawall near his house he was seized by the terrifying transports he’d thought to find in tool shed, in Communion-cup. The grass was alive! The town, the river, himself, were not imaginary; time roared in his ears like wind; the world was going on! This part ought to be dramatized. The Irish author James Joyce once wrote. Ambrose M — is going to scream.

There is no texture of rendered sensory detail, for one thing. The faded distorting mirrors beside Fat May; the impossibility of choosing a mount when one had but a single ride on the great carrousel; the vertigo attendant on his recognition that Ocean City was worn out, the place of fathers and grandfathers, straw-boatered men and parasoled ladies survived by their amusements. Money spent, the three paused at Peter’s insistence beside Fat May to watch the girls get their skirts blown up. The object was to tease Magda, who said: “I swear, Peter M —, you’ve got a one-track mind! Amby and me aren’t interested in such things.” In the tumbling-barrel, too, just inside the Devil’s mouth enhance to the funhouse, the girls were upended and their boyfriends and others could see up their dresses if they cared to. Which was the whole point, Ambrose realized. Of the entire funhouse! If you looked around, you noticed that almost all the people on the boardwalk were paired off into Couples except the small children; in a way, that was the whole point of Ocean City! If you had X-ray eves and could see everything going on at that instant under the boardwalk and in all the hotel rooms and cars and alleyways, you’d realize that all that normally showed, like restaurants and dance halls and clothing and test-your-strength machines, was merely preparation and intermission. Fat May screamed.

Because he watched the going-ons from the corner of his eye, it was Ambrose who spied the half-dollar on the boardwalk near the tumbling-barrel. Losers weepers. The first time he’d heard some people moving through a corridor not far away, just after he’d lost sight of the crack of light, he’d decided not to call to them, for fear they’d guess he was scared and poke fun; it sounded like roughnecks; he’d hoped they’d come by and he could follow in the dark without their knowing. Another time he’d heard just one person, unless he imagined it, bumping along as if on the other side of the plywood; perhaps Peter coming back for him, or Father, or Magda lost too. Or the owner and operator of the funhouse. He’d called out once, as though merrily:

“Anybody know where the heck we are?” But the query was too stiff, his voice cracked, when the sounds stopped he was terrified: maybe it was a queer who waited for fellows to get lost, or a longhaired filthy monster that lived in some cranny of the funhouse. He stood rigid for hours it seemed like, scarcely respiring. His future was shockingly clear, in outline. He tried holding his breath to the point of unconsciousness. There ought to be a button you could push to end your life absolutely without pain; disappear in a flick, like turning out a light. He would push it instantly! He despised Uncle Karl. But he despised his father too, for not being what he was supposed to be. Perhaps his father hated his father, and so on, and his son would hate him, and so on. Instantly!

Naturally he didn’t have nerve enough to ask Magda to go through the funhouse with him. With incredible nerve and to everyone’s surprise he invited Magda, quietly and politely, to go through the funhouse with him. “I warn you, I’ve never been through it before,” he added, laughing easily; “but I reckon we can manage somehow. The important thing to remember, after all, is that it’s meant to be a funhouse; that is, a place of amusement. If people really got lost or injured or too badly frightened in it, the owner’d go out of business. There’d even be lawsuits. No character in a work of fiction can make a speech this long without interruption or acknowledgment from the other characters.”

Mother teased Uncle Karl: “Three’s a crowd, I always heard.” But actually Ambrose was relieved that Peter now had a quarter too. Nothing was what it looked like. Every instant, under the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, millions of living animals devoured one another. Pilots were falling in flames over Europe; women were being forcibly raped in the South Pacific. His father should have taken him aside and said: “There is a simple secret to getting through the funhouse, as simple as being first to see the Towers. Here it is. Peter does not know it; neither does your Uncle Karl. You and I are different. Not surprisingly, you’ve often wished you weren’t. Don’t think I haven’t noticed how unhappy your childhood has been! But you’ll understand, when I tell you, why it had to be kept secret until now. And you won’t regret not being like your brother and your uncle. On the contrary!” If you knew all the stories behind all the people on the boardwalk, you’d see that nothing was what it looked like. Husbands and wives often hated each other; parents didn’t necessarily love their children; et cetera. A child took things for granted because he had nothing to compare his life to and everybody acted as if things were as they should be. Therefore each saw himself as the hero of the story, when the truth might turn out to be that he’s the villain, or the coward. And there wasn’t one thing you could do about it!

Hunchbacks, fat ladies, fools — that no one chose what he was was unbearable. In the movies he’d meet a beautiful young girl in the funhouse; they’d have hairs-breadth escapes from real dangers; he’d do and say the right things; she also; in the end they’d be lovers; their dialogue lines would match up; he’d be perfectly at ease; she’d not only like him well enough, she’d think he was marvelous; she’d lie awake thinking about him, instead of vice versa —the way his face looked in different lights and how he stood and exactly what he’d said — and yet that would be only one small episode in his wonderful life, among many many others. Not a turning point at all. What had happened in the tool shed was nothing. He hated, he loathed his parents! One reason for not writing a lost-in-the-funhouse story is that either everybody’s felt what Ambrose feels, in which case it goes without saying, or else no normal person feels such things, in which case Ambrose is a freak. “Is anything more tiresome, in fiction, than the problems of sensitive adolescents?” And it’s all too long and rambling, as if the author. For all a person knows the first time through, the end could be just around any corner; perhaps, not impossibly it’s been within reach any number of times. On the other hand he may be scarcely past the start, with everything yet to get through, an intolerable idea.

Fill in: His father’s raised eyebrows when he announced his decision to do the funhouse with Magda. Ambrose understands now, but didn’t then, that his father was wondering whether he knew what the funhouse was for — especially since he didn’t object, as he should have, when Peter decided to come along too. The ticket-woman, witchlike, mortifying him when inadvertently he gave her his name-coin instead of the half-dollar, then unkindly calling Magda’s attention to the birthmark on his temple: “Watch out for him, girlie, he’s a marked man!” She wasn’t even cruel, he understood, only vulgar and insensitive. Somewhere in the world there was a young woman with such splendid understanding that she’d see him entire, like a poem or story, and find his words so valuable after all that when he confessed his apprehensions she would explain why they were in fact the very things that made him precious to her . . . and to Western Civilization! There was no such girl, the simple truth being. Violent yawns as they approached the mouth. Whispered advice from an old-timer on a bench near the barrel: “Go crabwise and ye’ll get an eyeful without upsetting!” Composure vanished at the first pitch: Peter hollered joyously, Magda tumbled, shrieked, clutched her skirt; Ambrose scrambled crabwise, tight-lipped with terror, was soon out, watched his dropped name-coin slide among the couples. Shame-faced he saw that to get through expeditiously was not the point; Peter feigned assistance in order to trip Magda up, shouted “1 see Christmas!” when her legs went flying. The old man, his latest betrayer, cackled approval. A dim hail then of black-thread cobwebs and recorded gibber: he took Magda’s elbow to stead~’ her against revolving discs set in the slanted floor to throw your feet out from under, and explained to her in a calm, deep voice his theory that each phase of the funhouse was triggered either automatically, by a series of photoelectric devices, or else manually by operators stationed at peepholes. But he lost his voice thrice as the discs unbalanced him; Magda was anyhow squealing; but at one point she clutched him about the waist to keep from falling, and her right cheek pressed for a moment against his belt-buckle. Heroically he drew her up, it was his chance to clutch her close as if for support and say: “1 love you.” He even put an arm lightly about the small of her back before a sailor-and-girl pitched into them from behind, sorely treading his left big toe and knocking Magda asprawl with them. The sailor’s girl was a string-haired hussy with a loud laugh and light blue drawers; Ambrose realized that he wouldn’t have said “1 love you” anyhow, and was smitten with self-contempt. How much better it would be to be that common sailor! A wiry little Seaman 3rd, the fellow squeezed a girl to each side and stumbled hilarious into the mirror room, closer to Magda in thirty seconds than Ambrose had got in thirteen years. She giggled at something the fellow said to Peter; she drew her hair from her eyes with a movement so womanly it struck Ambrose’s heart; Peter’s smacking her backside then seemed particularly coarse. But Magda made a pleased indignant face and cried, “All right for you, mister!” and pursued Peter into the maze without a backward glance. The sailor followed after, leisurely, drawing his girl against his hip; Ambrose understood not only that they were all so relieved to be rid of his burdensome company that they didn’t even notice his absence, but that he himself shared their relief. Stepping from the treacherous passage at last into the mirror-maze, he saw once again, more clearly than ever, how readily he deceived himself into supposing he was a person. He even foresaw, wincing at his dreadful self-knowledge, that he would repeat the deception, at ever-rarer intervals, all his wretched life, so fearful were the alternatives. Fame, madness, suicide; perhaps all three. It’s not believable that so young a boy could articulate that reflection, and in fiction the merely true must always yield to the plausible. Moreover, the symbolism is in places heavy-footed. Yet Ambrose M —understood, as few adults do, that the famous loneliness of the great was no popular myth but a general truth — furthermore, that it was as much cause as effect.

All the preceding except the last few sentences is exposition that should’ve been done earlier or interspersed with the present action instead of lumped together. No reader would put up with so much with such prolixity. It’s interesting that Ambrose’s father, though presumably an intelligent man (as indicated by his role as grade-school principal), neither encouraged nor discouraged his sons at all in any way — as if he either didn’t care about them or cared all right but didn’t know how to act. If this fact should contribute to one of them’s becoming a celebrated but wretchedly unhappy scientist, was it a good thing or not? He too might someday face the question; it would be useful to know whether it had tortured his father for years, for example, or never once crossed his mind.

In the maze two important things happened. First, our hero found a name-coin someone else had lost or discarded: AMBROSE, suggestive of the famous lightship and of his late grandfather’s favorite dessert, which his mother used to prepare on special occasions out of coconut, oranges, grapes, and what else. Second, as he wondered at the endless replication of his image in the mirrors, second, as he lost himself in the reflection that the necessity for an observer makes perfect observation impossible, better make him eighteen at least, yet that would render other things unlikely, he heard Peter and Magda chuckling somewhere together in the maze. “Here!” “No, here!” they shouted to each other; Peter said, “Where’s Amby?” Magda murmured “Amb?” Peter called. In a pleased, friendly voice. He didn’t reply. The truth was, his brother was a happy-go-lucky youngster who’d’ve been better off with a regular brother of his own, but who seldom complained of his lot and was generally cordial. Ambrose’s throat ached; there aren’t enough different ways to say that. He stood quietly while the two young people giggled and thumped through the glittering maze, hurrah’d their discovery of its exit, cried out in joyful alarm at what next beset them. Then he set his mouth and followed after, as he supposed, took a wrong turn, strayed into the pass wherein he lingers yet.

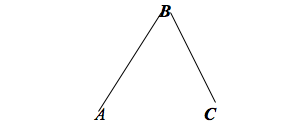

The action of conventional dramatic narrative may be represented by a diagram called Freitag’s Triangle:

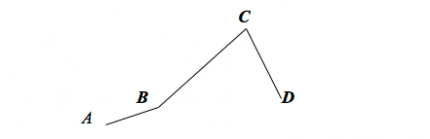

or more accurately by a variant of that diagram:

in which AB represents the exposition, B the introduction of conflict, BC the “rising action,” complication, or development of the conflict, C the climax, or turn of the action, CD the denouement, or resolution of the conflict. While there is no reason to regard this pattern as an absolute necessity, like many other conventions it became conventional because great numbers of people over many years learned by trial and error that it was effective; one ought not to forsake it, therefore, unless one wishes to forsake as well the effect of drama or has clear cause to feel that deliberate violation of the “normal” pattern can better can better effect that effect. This can’t go on much longer; it can go on forever. He died telling stories to himself in the dark; years later, when that vast unsuspected area of the funhouse came to light, the first expedition found his skeleton in one of its labyrinthine corridors and mistook it for part of the entertainment. He died of starvation telling himself stories in the dark; but unbeknownst unbeknownst to him, an assistant operator of the funhouse, happening to overhear him, crouched just behind the ply board partition and wrote down his every word. The operator’s daughter, an exquisite young woman with a figure unusually well developed for her age, crouched just behind the partition and transcribed his every word. Though she had never laid eyes on him, she recognized that here was one of Western Culture’s truly great imaginations, the eloquence of whose suffering would be an inspiration to unnumbered. And her heart was torn between her love for the misfortunate young man (yes, she loved him, though she had never laid though she knew him only — but how well! — through his words, and the deep, calm voice in which he spoke them) between her love et cetera and her womanly intuition that only in suffering and isolation could he give voice et cetera. Lone dark dying. Quietly she kissed the rough ply board, and a tear fell upon the page. Where she had written in shorthand Where she had written in shorthand Where she had written in shorthand Where she et cetera. A long time ago we should have passed the apex of Freitag’s Triangle and made brief work of the dénouement; the plot doesn’t rise by meaningful steps but winds upon itself, digresses, retreats, hesitates, sighs, collapses, expires. The climax of the story must be its protagonist’s discovery of a way to get through the funhouse. But he had found none, may have ceased to search.

What relevance does the war have to the story? Should there be fireworks outside or not?

Ambrose wandered, languished, dozed. Now and then he fell into his habit of rehearsing to himself the unadventurous story of his life, narrated from the third-person point of view, from his earliest memory parenthesis of maple leaves stirring in the summer breath of tidewater Maryland end of parenthesis to the present moment. Its principal events, on this telling, would appear to have been A, B, C, and D.

He imagined himself years hence, successful, married, at ease in the world, the trials of his adolescence far behind him. He has come to the seashore with his family for the holiday: how Ocean City has changed! But at one seldom at one ill-frequented end of the boardwalk a few derelict. amusements survive from times gone by: the great carrousel from the turn of! the century, with its monstrous griffins and mechanical concert band; the roller coaster rumored since 1916 to have been condemned; the mechanical shooting gallery in which only the image of our enemies changed: His own son laughs with Fat May and wants to know what a funhouse is; Ambrose hugs the sturdy lad close and smiles around his pipe stem at his wife.

The family’s going home. Mother sits between Father and Uncle Karl, who teases him good-naturedly who chuckles over the fact that the comrade with whom he’d fought his way shoulder to shoulder through the funhouse had turned out to be a blind Negro girl — to their mutual discomfort, as they’d opened their souls. But such are the walls of custom, which even. Whose arm is where? How must it feel. He dreams of a funhouse vaster by’ far than any yet constructed; but by then they may be out of fashion, like~ steamboats and excursion trains. Already quaint and seedy: the draperied ladies on the frieze of the carrousel are his father’s father’s mooncheeked dreams; if he thinks of it more he will vomit his apple-on-a-stick.

He wonders: will he become a regular person? Something has gone wrong; his vaccination didn’t take; at the Boy-Scout initiation campfire he only pretended to be deeply moved, as he pretends to this hour that it is not so bad after all in the funhouse, and that he has a little limp. How long will it last? He envisions a truly astonishing funhouse, incredibly complex yet utterly controlled from a great central switchboard like the console of a pipe organ. Nobody had enough imagination. He could design such a place himself, wiring and all, and he’s only thirteen years old. He would be its operator: panel lights would show what was up in every cranny of its cunning of its multivarious vastness; a switch-flick would ease this fellow’s way, complicate that’s, to balance things out; if anyone seemed lost or frightened, all the operator had to do was.

He wishes he had never entered the funhouse. But he has. Then he wishes he were dead. But he’s not. Therefore he will construct funhouses for others and be their secret operator — though he would rather be among the lovers for whom funhouses are designed.